I first met William Brown in spring 1997. I remember the year very clearly because, at the time, I was working with Ifor Davies and Iwan Bala on a Beca Artists project for the Abergele Eisteddfod. It was Ifor who repeatedly suggested that I contact ‘a very interesting artist’ now living not very far from where I grew up, Cefn Cribbwr.

On Ifor Davies’ insistence therefore, I sent the unknown artist at first a letter, then a postcard and then I phoned and left a message on his answer machine. I heard nothing back until a few weeks later when I found a message on my answer machine that used up all the minutes on the little micro-cassette-tape those gadgets used in those days. I wish I had that message today. I wish I had it because, as I was to find out, Mr William Brown was an enthusiastic communicator. When he was in the mood, he’d phone several friends in an evening, fill their message machines with barely decipherable spoken information and usually follow the phone-call with an equally scatter-graphed written message featuring, sketches, stickers, jokes, quotations, rubber stamps, and random enclosures. William burned like St Elmo’s Fire. He was an omen. His now luminous, now dark transmissions were, for me, always an inspiration.

When we finally spoke in person, over the phone, the signs weren’t good. William had learned from Ifor that I made small books and he was looking for someone with whom to make something ready for the Bridgend Eisteddfod in 1998. “What kind of book?” “Folktales,” he replied. “What kind of folktales?” asked I of this slightly, high-tenor Canadian voice whose embodied presence I was yet to encounter. The torrent that followed concluded with, “The story of Gelert, that kind of thing.” I’d heard enough and told the voice, “I’m sorry I think you’ve got the wrong bloke.” The voice grew instantly ferocious and snarled, “Wassamarrer you’ve seen a dead dog ain’tcha?” And this became one of the qualities I most admired about William – his no nonsense ability to be direct, whether challenging and offensive or even directly tender and childlike. We arranged to meet.

Prior to the meeting and regardless of our unlucky phone call, I received the following letter.

Our meeting at Chapter Arts Centre soon afterwards came on a day when William was still teaching adult art lessons at various locations around south Wales. He had the knack of finding teaching contracts and of securing grants. I quickly learned, however, that he could be very uncomplimentary about the Arts Council or any other hand that feeds. He could also be caustic about the pretentions that hover around places like Chapter with its often minimalist yet inflated, conceptual indulgences. One of his favourite jokes was, “Art Therapy, I need it, how I can be expected to teach it.” We agreed to meet at Llangynwyd the next time I came to visit my parents in nearby Cefn Cribbwr.

One of the early letters I received from William complete with an entire family of motifs. Bear, doorway, Mari Lwyd, toy, puffin, skeleton and jokes. There is no Venus of Blaengwynfi among these 1998 doodles.

During these early meetings I could see that William was giving us both an opportunity to display our work before a very specific local audience. Should we organize a Bridgend Eisteddfod stand for the Pencoed location in 1998, it was likely that we would personally know many of those who might be interested in his paintings, my writing and ‘our book’. The project was on.

I suggested that we call our book March. This name was at least pronounceable in Welsh and in English, even though the final ‘ch’ should be pronounced as the ‘ch’ in loch. March is a Welsh word that translates as stallion or charger, and it was as ‘charger’ that we intended it. ‘Ysgall’ for example translates as ‘thistle’ and ‘march ysgall y gerddi’ translates as artichoke – or ‘super thistle of the gardens’. It was in the sense of horse ‘power’ that we chose this word.

The cover was a profile lino print of the Mari Lwyd transformed into a dancing dervish. The first full page print would be a more melancholy looking Mari standing forlornly in white space. I felt March reflected the compelling, underlying priorities of his work in the sense that it meant ‘relentless’ and ‘exuberant’.

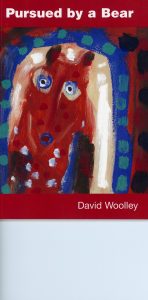

March, front and back

William’s studio was located in what was once St Stephens Church in the Parish of Llangynwyd. St Stephens was part of a circuit of five churches including the locally famous St Cynwyd’s up in the hilltop village. St Stephens stands across the road from a housing estate on the main Bridgend to Maesteg road. But, as William loved to relate, his studio was technically in Pontrhydycyff, as it was across the road from the estate and therefore in another village. The building had, until very shortly before he moved in, served as a school and church. William delighted in local knowledge and the local road-crossing, lollipop man Colin would often call to share scandal, jokes and gossip. As an inveterate letter writer and mail artist William also formed a very close friendship with Gill and Gwyn Evans and later Tal and Daphne Harries at the post office, just the other side of a bus shelter, barely fifty metres from the studio. Gwyn Evans kept a Mari Lwyd under the bed and was Groom for the local party. This was the Mari most closely linked to William’s knowledge of this custom.

William travelled by bus almost everyday and loved to eavesdrop on other people’s conversations which he would repeat, complete with local accent. But as well as being the haunt of schoolchildren the bus shelter had a less savoury side involving under-age drinking, urinating, sniffing glue and so on. Someone from this gang attacked the studio several times, and even attempted to burn it down. One day William went out with black paint and painted a great bear on the bus shelter inside wall. The arsonist was arrested and given a two year sentence while the painting lasted until the bus shelter was replaced by a structure of plastic and glass.

A bear very similar to this was painted in the bus shelter. Not the alchemical shapes, heart, spiral and Shackleton’s ship

I soon noticed that it was because William was so confidently international that he loved the parochial. He loved the vernacular of this tiny corner of the world – Bridgend, Llangynwyd, Pontrhydcyff, Maesteg. He became a language student of writer and Welsh teacher Colin Williams and made several books with him, among them the bipolar Good Dog Bad Dog and the truly hilarious, Elastic Black Dog, which was based a nightmare William’s wife Carys had had of a dog performing bunjee leaps outside their window’.

All of this became apparent as we met over a fifteen month period leading to the 1998 Eisteddfod. I wrote a number of poems and William cut images in lino. Some of these intaglio blocks were up to half a meter square, printed on large sheets of thick, archival paper. Many times when I called by, new prints would be fixed by clothes pegs and hanging from lines inside the cold, cavernous church, a building which never warmed up even in summer. The visits were thrilling, inspirational, and as the prints progressed we invited the editors of Welsh language magazine Barn to come and see them. Barn featured March in the double issue 426,427 (July/August 1998 pages 50 -55). And, thanks to critic Laura Gascoigne, William’s painting Barbary Coast was featured on the cover of Artists and Illustrators (September 1998, number 144), the very week our book was launched.

He had that felicitous touch.

During the nine days of the Bridgend Eisteddfod, March sold out. It may have been a mistake to do a second edition, but eventually these copies sold too and we made more work as a writer-artist partnership.

William’s working method was a high-energy combination of steady, bull-headed production (often making and repeating several canvasses at a time) with explosive bursts of experimentation. Many times I watched him cut a lino block with rapid accuracy – marking out the main image and then finishing it with gouges, lines, rays, dots and other marks that transformed a depiction into an animated metaphor. My close friend and printmaker Peter Hay in Reading commented many times how he admired the unaffected nature of these prints.

The recurring motifs in this print reappear in other paintings, doodles and sketches: triangle, spots, spiral, heart, hand and whisker-like fibres, with little attempt to conceal the gouging chisel action that cuts the lino. This print did not appear in March but was made in response to the poem Crogi Llygoden.

Loup Garou in pram. The motif of the wheel is also important. Note the black white contrast of line – black for the handle, white for the spokes. Lino block residue is given importance in the composition.

William worked quickly but he also nurtured other uses of time during which he supported his creativity with practical tasks such as making stretchers, priming canvasses, writing letters, making phone calls and travelling to see the work of others.

At this time William was making superb prints of the Mari Lwyd representing the tradition as a blended, seamless horse/human figure. William was never an artist who simply characterised the Mari Lwyd as a puppet from Welsh folklore. In paintings the acrylics were applied with spalter brushes which made them chromatically bold and free of detailed line. Meanwhile, quite apart from their graphic quality, the black and white prints captured the animated Mari with unusual linear economy and range of feeling. The subject and style could flip from idiom to idiom.

March, facing page

I saw William’s Mari work as connecting with a mythic force. To me the Mari Lwyd paintings are semi-abstract compositions that provide an opportunity for daubs of paint or coup de couleur., The etymological significance of daub, to plaster lattice with muck (and shit) was an aspect he emphasised in conversation. In many of the Mari paintings the bold application of coloured marks, stripes, smears, speckles, circles and blotches may look as if they resemble a horse’s skull wrapped in a sheet – but they could also be regarded as near magical charms, much like the cave painting of northern Spain that he admired so much and visited. The more basic the smear or mark the more powerful the picture. Over the years that we knew each other, we discussed this. I almost came to think of these paintings as visions where the Mari actually withdraws and William Brown, the magus, appears in their place.

The Mari Lwyd as Canadian Moose appears a doorway.

Our first book, March comprised eleven poems each with its own facing visual image. Including the cover and title page there were ten other incidental prints. The Mari Lwyd on page four was lost (possibly stolen) when William gave a workshop at St Donat’s Arts Centre with the result that March is the only place where this restrained but powerful print is featured.

March, page four – the intaglio that went missing

William was very precise about the way he wanted the book to come out. We agreed that it should be vertical in order to accommodate the verses. Apart from that he specified that it should be on thick card and spiral bound. He wanted the tactile feel to be that of a child’s notebook. Regarding the vertical, rectangular opportunity that the book provided, this was when I saw how mischievous William could be. The designer and I repeatedly asked William for images that would best exploit a vertical format. But very often the material sent obeyed another voice and did not conform to what felt like our petty demands.

Regarding other details, I received editorial support from poet T. James Jones and novelist Manon Rhys. Hywel Teifi Edwards provided a rear-cover comment. This connection came about because William’s father-in-law, Herbert John Davies while headmaster of Garw Grammar School had given Hywel Teifi his first job, there. The book came out looking better as a result of these idiosyncratic but meticulous demands.

Norman Harris, the owner of Harris Printers in Porthcawl, sponsored the book. Carys provided tables, wire racks and other gear from her school and we prepared for our stand at the Eisteddfod. It was during the Eisteddfod that I first experienced William’s extraordinary generosity.

The Eisteddfod is a curious festival that warms up quietly on the first weekend, becoming more intense as the week goes on. This wasn’t our experience. Our unit was busy from the moment it opened on Saturday morning the 2nd of August 1998. One of the reasons we had so many visitors could have been the hand-painted canvass banner William has made, featuring a portrait of the Mari Lwyd. We even called the unit Y Fari Lwyd which caused some irritation. We recruited a flow of volunteer cashiers to sit among bunches of flowers and did our best to look presentable.

Stock comprised our joint new book March, another new book of mine Yr Wyddor, earlier books, boxes of William’s watercolours, portfolios filled with prints and with larger canvasses gently rocking on the canvass walls. It was a magnet for anyone with an eye for art.

When William noticed that I was diligently noting down every individual sale, such as one copy of our new book March at £3:95 or one print by him at £45, he took me to one side. And, as a good Canadian, his speech was speckled with the occasional ‘Go figure.” Sentences often ended with ‘eh?” especially when he was nervous. “So we split everything down the middle eh?” I didn’t quite follow. “Everything we take, whatever we make, we divide it eh? Equally?” He was serious and I couldn’t persuade him otherwise. That’s the way it remained for all the years we worked together – fifty-fifty. If I sold books to the value of a hundred pounds and he sold paintings to the value of a thousand, that meant we took £550 each. I found this astonishing, but it also meant that we formed a practical attitude and alliance. Many times I found myself promoting William’s work without being connected with his project. He was equally loyal, inviting me to read at innumerable exhibits from Pontardawe to Plymouth, Llantrisant to London, from Ogmore Vale to Ottawa.

The first days of the Eisteddfod passed busily by. I had also been commissioned to read at a Ceredigion kitchen stall and twice a day I also performed Yr Wyddor at a purpose-built theatre provided by the Arts Council of Wales, managed by theatre company Cwmni Da and financed by a Lottery grant. The Mari Lwyd unit on the other hand, relied on our own commercial graft and acumen.

The Yr Wyddor theatre/video installation had steadily become infested by stress and ego conflict. The other artists involved had co-opted what was supposed to be a communal project to their own individual ends and one was even claiming ownership. The spite was dreadful. Even so I dutifully broke away from William every morning and afternoon and recited the book length abstract-minimalist poem to the drone of an Indian tambura.

Often when I returned to the Mari Lwyd space William had transformed our unit from a sales marketing stall, as I conceived it, into a social event, as he enjoyed it. He delighted in wearing hairy, wolfman gloves and would sometimes put on a full head-covering, latex, wolf’s mask. The loup garou werewolf tradition of French Canada entertained him hugely and a leaping wolf featured in many of his paintings, prints and drawings. I became a fan of this childlike aspect and felt that, as much as playfulness, it was also participatory research where William entered into the souls of the cast of characters that visited his work.

One afternoon when I came back from the drudge that working with Tim Davies at Yr Wyddor had become I found William chatting to a lady in our stall. She was clearly one of those slightly senior dames without whom many an eisteddfod project would not get off the ground. She took a coquettish interest in the work and asked lots of quietly flattering questions. As our guest moved from picture to picture and perused the books and portfolios, the large buttons up the front of her summer dress, slowly came undone. Eventually almost every button except perhaps the one at the very bottom and a few at the top became unfastened. How aware was this woman that William and I were now talking to her petticoat? Finally Janet Francis, our cashier for that day, told our alluring visitor that she was visible to the world in a state of demure dishabille. To our amazement our visitor did not blush or turn away but stared calmly at us, as one by one, she slowly did each button up. Janet confirmed that this display had not been our imagination. We never did find out who this delightful exhibitionist was but she left with watercolours and books, leaving behind an atmosphere that charmed our tent for the remainder of the festival. This experience later became the subject of my poem It Was Good to See You (in Weak Eros). It may well have been a prompt for William when he later suggested – “Let’s make something erotic for the millennium eh?” Which led to The Love Letter – a small book snugly packaged in a plastic sheath and brown paper envelope.

It was a memorable week, William sold some canvasses and we came to know each other more. After a long day, some evenings I’d go back to his house in Bridgend and this was also when I started to know Carys. Carys was clearly delighted that our collaboration was going this well. The dining room in Bridgend had a huge plank table piled on one side with books, letters, magazines and photographs leaving space on the other for a bottle of wine or a meal. This impressive table emanated a love not only of food, drink and entertainment but also children, grandchildren, friends and visitors.

Staffing a unit at the Eisteddfod on a daily basis can be quite tiring but we were buoyed up by the very positive response our contribution had received. It wasn’t all sunshine though. Our appropriation of the Mari Lwyd provoked a reaction. We had Maris at the entrance to our space and a third at the back. Staff connected with the TV drama series Pam Fi Duw asked to borrow two of these for some filming they were doing that week. The trouble is they weren’t returned as agreed. I had to argue very forcibly with David Meredith, senior administrator of the Eisteddfod that day, that he should help me get them back. This was a nuisance which briefly robbed our unit of dramatic impact.

We also had a visit from some members of Cowbridge Male Choir. They seemed to feel that that they had a copywrite on the custom and were upset that we were using it for our own devious ends. This happened with other visitors from Vale of Glamorgan villages. But rather than be bothered by these mildly pugnacious visits we were pleased that the tradition was being maintained at more locations that we were aware of. Musician and Mari Lwyd specialist Mick Tems took a great interest in this territorial news and wrote about it for Taplas magazine. With Pat Smith he also sang in front of our space which attracted more audience attention.

Because of these and many other encounters the Mari became an even more absorbing subject. A phenomenology of the Mari was being captured, as if the tent were a lure. Other stories were caught there too. In the years that followed William made many paintings featuring the curtained stage of our canvass cabin. These paintings form a mise en scene with characters appearing as if the stage were a temenos (or llan) enclosing all kinds of figures and spectres, from matriarchs and demons to animals and ghosts – or as William referred to them, as visitors.

Curtained stage scene with Mari Lwyd, Venus of Blaengwynfi, moon and (half) Loup Garou (with heart) leaping in from right.

The idea of an otherworldly visitor at the threshold is a recurring theme of William Brown’s art and the Mari Lwyd provided an opportunity for depicting such apparitions. In this regard the Mari becomes a liminal being and there is no doubt that this is how William regarded it2. Even though a final explanation of the Mari Lwyd folk custom remains unresolved William refused to reduce it to folk residue. Even if misguided we both constantly sought to broaden our interest in this mid-winter ritual rather than view it as a quaint, pastoral relic. Why not take this horse figure back to the cult of Epona and revisit its potential as an animal/human guide? Liminal beings can be both dangerous and benevolent and this fearsome duality is present in William’s hybrid horse-human portrait.

The Bridgend Eisteddfod in 1998 was a week long welcome of strange outsiders but, fortunately, most them appeared in human form. Canvasses following the Eisteddfod featured the drapes that William had made for our stand. In these paintings a stage with curtains serves as a frame within a frame. It is also a Dionysian arena visited by, among others, the Venus of Blaengwynfi, the Loup Garou, the Mari Lwyd and in many canvasses bears, mummies, lovespoons and toys. Characteristically, William later merged the concept of festival with the more modest occasion of charity fete or village kermesse. His close friend, poet Lucien Suel often organised events at his home near Lille, calling them QAGs, which was a parody of a corporate bonding event (Quality Assurance Group) that Lucien’s son once had to endure. William loved Lucien’s domestic festivals which included anything from rock music to portrait sketching (changing shape, changing appearance) to cooking for groups of people (transforming food, transforming mood). Even though sometimes very shy William could also play a central role in communal gatherings of this type. While he did face sketching Carys made Welsh cakes.

Even though I’d seen them many times, and had recently seen William’s show (Beyond the Loup Garou) assembled by Sandra Jackerman at Newport Museum Art Gallery it was during the week of the 1998 Eisteddfod that I truly came to appreciate his paintings. It dawned on me how important Canada was to his sense of the north, the wild, to the French language and to landscape. Even though he now lived in the much more compact environment of Wales I sensed that his need to travel – to places like Spain, Greece, Morocco and Tunisia, refreshed his pleasure in other conditions of space and light. Following the Eisteddfod I looked at his canvasses with new eyes.

William repeated themes, motifs, images and content, working through ideas and developing them in series. The black and white squares he sometimes painted flip between paradoxical interpretations as much as any other motif in his work. The black and white squares can be seen as the site of chess, which he regarded as a game of love in the medieval tradition of Scachs d’Amour; but it could also be read as a masculine spiritual location representing as it also does the ritual Masonic floor. One of William’s more radical characteristics was that while being a disciplined anarchist he was also a freemason. If I asked him it if was a chess board he would agree (and amplify); but if someone else identified it as a Masonic space, he would agree with that as well. He enjoyed depicting “those stones that had been rejected”.

Motifs: dotted side bars, cordate heart, tartan bicameral wolf, chequered field.

During our ten day stint I’d seen William in a variety of moods, always attentive, sometimes melancholy, and other times filled with vivacious joy. Now, when I looked at his work I recognised signs of isolation and exile in the Moose Among Pines. William had a metaphoric and a literal imagination and there was the moose’s heart – in one canvass a radiant cordate shape inside the body but in another the heart lays fallen and bleeding in the snow.

White heart within the moose, red heart in the snow

When I looked at his many bears, in tartan, with sacred hearts, cut in half – I thought of his background, conceived in Scotland, born in Canada and felt that this blended identity had given him a love of compound themes. The repeated presence of the Great Bear constellation above Welsh chapels, terraced streets and many times simply as a semiotic shape, stamps his work with a love of simplicity but also with a love of north, of night, of space, and of the zoomorphic human interior that his totemic devotion to The Bear made possible.

Bear emerging from terraced houses, with chapel. Motifs include cordate heart, speckles and dehiscent edges, moon, windows. The title of this painting is New Guy in Town, confirming (as he said in many statements) how William perceived himself as a bear.

The Eisteddfod came to an end and we had made quite a bit of money. We’d sold over 400 copies of a book that (thanks to Norman Harris’ sponsorship) had cost us next to nothing to produce. We’d sold other books, prints and paintings. I had fallen into the role of secretary-treasurer and it was with some relief that on Saturday evening the 9th of August, seated at their commodious dining table, I showed Carys our sales record and proceeded to count the money out.

There were sides of William many of his friends did not know even up to the day he died. What I hadn’t known, until that evening, was that he had a vehement disregard for money. “Oh no!” Carys cried out, “You’re not giving him cash! David you mustn’t do that!”

But it was too late. William already had the money in his hand and almost squealing like a child he was promptly putting it in different envelopes. “Right, I’ll send this to Goble, this to Kathleen, this to Malcolm . . . .2 ” continuing his litany until all the money was packaged and his hands were empty. It was as if the money had to be thrown from his hands as quickly as possible. Carys didn’t interfere and when this almost phobic display was over we returned to our review of the week.

Looking back there had been signs of a strange relationship with money but it seemed like a kind of game. We’d sold books, prints and paintings for cash and cheque but William, instead of taking payment himself would playfully point a customer in the direction of our assistant who’d be sitting under a horse’s skull at the rear of our tent. I soon did the same, jokingly telling people that we’d both been advised by our Taoist Doctor not to touch cash. This was a ploy that kept all of us employed – our helper recording sales and giving change while William and I welcomed people into our always busy space. It was important to be gracious and welcoming as many people clearly liked the art but some found it strange and might leave, feeling unable to engage. If William did the talking he referred to me as his writer-collaborator; if I made the opening then I would refer to him as my painter-friend. This always eased the seller/buyer relationship and when it actually avoided touching money made it seem like more of a gift exchange than a sale. In any case William was an extremely charitable individual.

One sunny afternoon we were visited by three or four young women who turned out to be art teachers. They’d been through college together and were now attending the Eisteddfod as a group. They liked our unit and took their time looking through William’s boxes of drawings and watercolours. After making their choices he gave a price which they found astonishingly reasonable even foolishly cheap and turned to me as if to ask if they could offer more. We compromised by inviting them to choose a few more small paintings and thus pay a slightly higher price. William was satisfied with this. He’d sold more work, generated more goodwill and commented that he loved to think of his art being found on the walls of appreciative homes.

This aversion to money was however symptomatic of a much more complex side of William’s character. He loved to give and often presented a friend with a novel or CD or souvenir from his travels. He also gave gifts of drawings or drawing materials to the children of his friends. He routinely donated work to charity auctions. He was interested in the tradition of sin-eating and its twin custom of placing money in the mouths of the deceased, at their feet or on their eyes. Those who choose not to touch money often do so for reasons of ritual purity but I don’t believe William was that pious or that pretentious in any way. His extravagance with money was I think connected with his love of chance and of living outside conventional boundaries. He was, as they said in Samuel Johnson’s day, a devotee of Deep Play, which is often a commitment to chance and risk that many people would avoid. Diane Ackerman3 has described it as ecstatic, rapturous and transcendental. Perhaps it’s also manic. Its melancholy shadow was found in Sombre Kermesse.

Motifs: mummy, lovespoon, bear in doorway, half bear entering from right, great bear constellation, moon, cordate heart, chequered field, toy, half loup garou (leaping from left) Venus of Blaengwynfi, tartan, stripes, dots.

William would follow wherever circumstances led. He enjoyed parties and was an extremely professional figure at the social opening of his exhibits. Going into the pub William was always the first to buy a round, including a drink for whoever served him at the bar. When he organised a group show there was always food and drink even when no one else contributed. But he was nobody’s fool, if he felt that a buyer was trying to haggle a price down out of greed rather than frugality then he wouldn’t budge and inch.

And so, that evening, I watched him give a lot of money away and I saw it more than once. Our week was over. I didn’t know what to expect and felt more or less that we’d leave the possibility of any collaborative future work to fate. But it wasn’t to be that way. I was leaving for America in two days time to join my family on holiday. On my return William insisted I must certainly call up and see him at the studio in Llangynwyd. He had other projects, other plans and other ideas – not only for me but for his other collaborators – constantly in mind.

1 See the work of Victor and Edith Turner.

2Tony Goble artist; Kathleen Hommel, his sister;, Malcolm Parr poet.

3see Deep Play by Diane Ackerman.

5082 words